Zafor Alam (62) lives in Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh. He normally earns a daily wage of 500 taka ($6 US) by selling tea and biscuits but has not been able to earn a single taka since the lockdown was enforced in April. Zafor understands the importance of the lockdown to contain the spread of Coronavirus in the overcrowded camps, but he recently told one of my colleagues in Bangladesh:

‘We might die of hunger before coronavirus, so how are we meant to stay alive?’

In addition to his lack of income, the price of groceries has increased during the pandemic and there is a shortage of supplies. Zafor couldn’t afford to stock up on food before the lockdown began and is now desperately worried about how he will feed his wife and family going forward.

Lockdowns in rich countries around the world have caused economic disruption to many, especially the poorest populations, but for older people living in low-income countries, they can be a matter of life and death. Older people are expected to keep themselves safe at home to avoid the risk of contracting COVID-19, but many of them still depend on going out to work in order to put a meal on the table or buy other essentials.

Umm Imad (75) lives in the Gaza Strip and suffers from high blood pressure and diabetes. She normally earns enough money by buying second hand clothes, washing and ironing them and reselling them at a higher value to pay for the medication she needs. But the coronavirus lockdown means she is no longer able to do this. She has had to cut back on her medication she takes and is worried that she will be forced to beg in the streets when she has to reduce her medication below critical levels.

Desperate stories of older people like those from Zafor Alam and Umm Imad who are struggling to survive amid coronavirus can be heard across the globe.

Older people have always been vulnerable to poverty in low income countries but the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated pre-existing inequalities, ageism and discrimination, as well as the challenges faced in accessing humanitarian assistance.

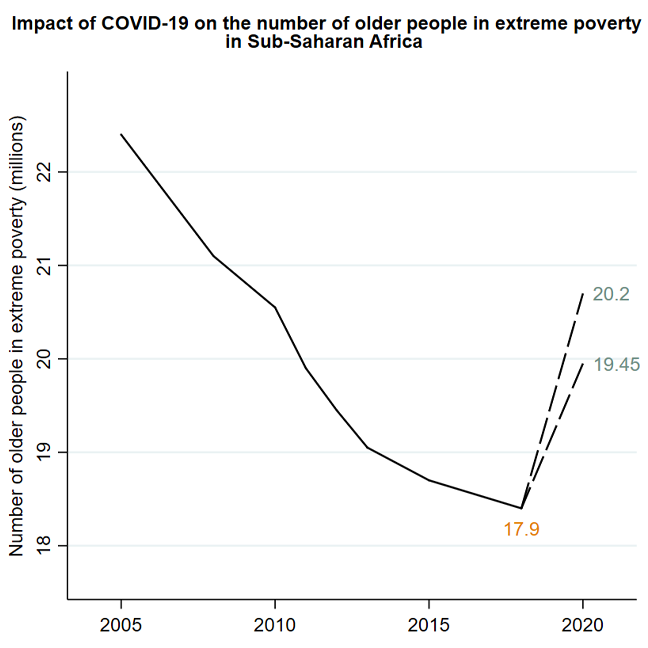

Indeed, analysis from the World Bank released last month predicts that close to 50 million people will be pushed into extreme poverty – living below a USD 1.90 a day – due to COVID-19. Estimations by HelpAge on the basis of World Bank data suggest that in Sub-Saharan Africa alone between 1.6 and 2.3 million more older people will become destitute as a result of the crisis.

The reality is that millions of older people who live without the support of a pension may never recover from the loss of livelihoods and income caused by the lockdowns imposed in response to COVID-19.

The shutdown of markets and other ways of earning money have taken financial autonomy away from older people who rely on the small income they or their family members are able to earn.

Kadiatu Kargbo (72) from Freetown in Sierra Leone was supported by her eldest daughter who works as a nanny. Unfortunately her daughter was asked to not come to work until the pandemic is over and, struggling to provide for her own children, is no longer able to support her mother.

Valentina Petro (63) from Mwanangi vikage in Busega district in north west Tanzania has an amputated right arm following accusations of witchcraft and is dependent on her three daughters. One is a farmer, another sells fish and the third sells second-hand clothes. None of them are able to earn a living as the markets are closed and the whole family is rapidly running out of money.

Unsurprisingly, this can make tensions run high in families, with many having to choose between whether they support their children or their parents. This leaves older parents feeling like a burden.

A colleague from HelpAge India recently explained how he gave a food parcel to an older man who told him ‘for the first time in a very long period my family will appreciate me. I’m just seen as a burden as I can’t contribute to the household’.

These tensions are also leading to an increase of domestic abuse of older people in many countries. Helpline staff for HelpAge India are reporting a marked increase in calls from older people experiencing domestic abuse and similar cases have been reported in countries like Jordan and Kenya.

One of the major problems compounding older people’s poverty in low income countries is the lack of social protection and in particular the absence of pensions in many countries. Only 22 per cent of governments in Sub-Saharan Africa provide pensions and only 23 per cent in South Asia, while many countries have done nothing to support older people to help them through the COVID-19 crisis.

Some countries – like Kenya and South Africa that do guarantee pensions for all older people – have paid out additional sums to support older people through the COVID-19 crisis. As of 23 April, 39 countries have adapted or expanded old age social protection in response to the pandemic and while this is to be commended, it is a drop in the ocean compared to the millions who are at risk of poverty and starvation.

We have also heard from several countries in the world where older people could not access social protection or emergency cash transfers due to them as they did not have mobile phone or Internet banking and couldn’t go to the bank to collect the money because of the lockdown.

International aid agencies have, as they have done in all emergencies, stepped into help people in low income countries as a result of the Coronavirus pandemic, but older people often struggle to access this support, even though in the case of COVID-19, they are the most at risk. Anatole Bandu, the director of HelpAge in the Democratic Republic of Congo explains how it is difficult to access funding for older people even though older people are most at risk of developing serious illness and the overwhelming majority of people who are dying from the virus are aged over 60.

Unless pensions are more universally adopted and responses to COVID-19 – from governments or humanitarian agencies – start to be inclusive of older people, millions will be driven deeper into poverty and destitution and more lives will be needlessly lost.

But it won’t be COVID-19 that kills them. It will be a lack of medicines and starvation, brought on by extreme poverty, insufficient social protection and humanitarian agencies not responding to their specific needs.

A shorter version of this article was published on Thomson Reuters Foundation:

https://news.trust.org/item/20200511102348-9pf06/