Following Duncan Green’s (Head of Research at Oxfam GB) blog post “What does global aging mean to development?” (his spelling, not mine), I was more than happy to take him up on his kind offer of writing a response as a guest blog on From Poverty to Power:

Following Duncan Green’s (Head of Research at Oxfam GB) blog post “What does global aging mean to development?” (his spelling, not mine), I was more than happy to take him up on his kind offer of writing a response as a guest blog on From Poverty to Power:

The scale and speed of global population ageing are staggering. The recently launched Global Preparedness Index says “Worldwide, life expectancy at birth has increased by twenty-one years since 1950, a bigger gain over the past sixty years than humanity has achieved over the previous six thousand”.

And as the “Foreign Policy” article you quote notes, this is not just a rich world phenomenon. The combination of falling birth rates and extended life expectancy is a pattern nearly everywhere. Even sub-Saharan Africa, despite the impact of HIV and AIDS on life expectancy, will have 160 million over-60s by mid-century, the same as Europe’s older population now. Nearly one-third of the 59 countries which are below replacement level fertility are classified by the UN as “developing”, and even in the poorest countries women are having fewer children.

So what does ageing mean for development? Will low and middle income countries grow old before they grow rich? What can be done to meet the challenges of the global age wave, and especially for the older poor?

The missing “middle generation” and its impact on older people

Ageing is largely absent from development debates and action, yet it has impacts across many areas of development. Take migration. A major pull factor of international migration is the ageing of work-forces in the rich world; at the same time migration from poor communities leaves behind disproportionate numbers of the old – and the young.

From Latin America to Asia migration has changed the age profile of relatively “young” countries, leaving “skipped-generation” households of older people caring for grandchildren left by middle-generation migrants. With remittances infrequent, inadequate or non-existent, old and young in these households are sharing poverty and vulnerability.

The same effect is seen in sub-Saharan Africa, where in a number of countries grandparents of children orphaned by HIV and AIDS are the main care providers (in Zimbabwe and Namibia 60% of orphaned children are cared for by their grandmothers).

Ageing farmers

Look at rural development, where effort is on improving the productivity and incomes of small producers, but little attention is given to including older farmers. This matters, because many poor countries are seeing the ageing of their farming populations.

In Mozambique, over two-thirds of the members of the Small Farmers’ Union are over 50, a pattern repeated in the Caribbean and elsewhere. But older farmers in many countries say that they are excluded from programmes because they are seen as “too old” to benefit.

“Age friendly” healthcare?

Finally, think about health. Little effort is made to make health care “age friendly” despite the promotion of this approach by the World Health Organisation. For example, reproductive health programmes largely ignore the fact that multiple pregnancies in poor health conditions mean that many poor women spend their old age with chronic, life-limiting, but treatable conditions. So we need ways forward to tackle the challenges of an ageing world. Firstly we need to see older people not as a problem but part of the solution. Older people in poor communities are survivors, with lifetimes of experience to contribute. Enabling older people to organise has had a dynamic effect not only on improving their own lives but also on the wider community.

Older people’s groups in rural north India for example, have drawn in other community members to campaign for village schools. In the Philippines and Bangladesh, older people’s groups have played a key role in the initial response to climate emergencies, providing help to the most vulnerable before the arrival of humanitarian relief.

Lifetimes of experience and skills

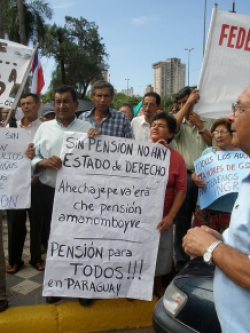

Income and health are older people’s priorities everywhere. Providing secure work for those who are able, and a pension for those who are unable to work is critical. Most poor people work far into old age; with lifetimes of experience they have skills to hand on, given the opportunity. In rural Kyrgyzstan for example, older community groups are financing their activities by providing “consultancies” to younger farmers on agricultural techniques.

The rise of chronic diseases has meant that in many poor countries more people are dying from heart disease and cancers than from communicable diseases. Yet the focus remains on the latter. Implementation of the WHO’s strategy would have a major impact on chronic disease, not only improving older people’s health but also that of middle generations who will otherwise age with chronic illness. A pilot health screening programme for retired plantation workers in Sri Lanka shows what is possible – identifying and treating hidden health problems, helping to avoid later crises.

Today’s 2050 generation (those who will enter old age at mid-century) will be the policymakers and professionals driving change in all fields of development. Demography is not destiny, and the choices they make will decide how successfully the world ages.

Read more about HelpAge’s work on health, pensions, work and HIV and AIDS.