When considering where to launch our keynote report on the opportunities and challenges of an ageing population, it quickly became clear that Japan was the ideal location. It was not just that Japan has a higher percentage of older people than any other nation. It was also the welcome lead this country is giving in embracing the remarkable and global demographic transition underway.

When considering where to launch our keynote report on the opportunities and challenges of an ageing population, it quickly became clear that Japan was the ideal location. It was not just that Japan has a higher percentage of older people than any other nation. It was also the welcome lead this country is giving in embracing the remarkable and global demographic transition underway.

Japan is the only nation with over 30% of its population aged 60 or above. However, by 2050, more than 60 countries are forecast to have passed this milestone. In every continent and in societies at all stages of economic development, we are living longer. Improved diets and sanitation, medical advances and greater prosperity have all increased life expectancy. This coupled with low fertility, means a completely new demographic landscape.

Population ageing in the developing world

There are, of course, marked differences in life expectancy between and within continents. Very few countries can compare to Japan where a girl born today can expect to live until she is 86. But the overall trend is strongly upwards almost everywhere. Indeed this change is happening fastest outside the most developed economies. By 2050, an estimated 80% of the world’s older people will live in developing countries.

The fact that we can look forward not just to living longer than previous generations but that these extra years could be enjoyed in good health should be a cause for celebration. Too often, however, this extraordinary achievement is seen only as a burden.

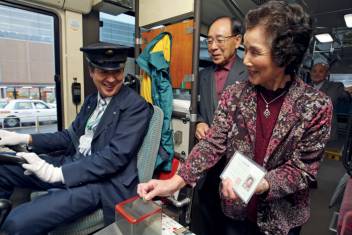

This is where Japan has much to teach the rest of the world. Thanks to a culture which includes a strong respect for older people but also through far-sighted policies, Japan is showing the benefits of an active, secure and healthy ageing population. There are five times as many older workers in paid employment as in France and older people are encouraged to participate in voluntary work.

Challenge of long-term care for older people

But even in Japan, the growing number of older people and the increasing demand for long-term care presents social, economic and cultural challenges. There are fewer children to look after parents, putting the intergenerational support system under stress. How we choose to address these challenges and maximise the opportunities of a growing older population will determine whether society will reap the benefits of the longevity dividend.

It was to see how this can best be achieved that the United Nations Population Fund and HelpAge International brought together the expertise of over 20 UN and international agencies, to examine what is working globally, to share best practice and to identify implementation gaps. What makes the report unique is the focus on older people’s views and what was striking was their common desire to remain active and be respected contributors to their society.

New policies needed to adapt to demographic transition

The result is the report “Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and A Challenge”, which we are launching in partnership with HelpAge International today in Tokyo. It shows that a great deal of progress has been made by many countries in adopting new policies and strategies on ageing but much more needs to be done.

In particular, the report found three areas where change is needed if we are to ensure a society in which both young and old are given the opportunity to contribute to development and share in its benefits. First, there is an urgent need to guarantee income security and access to essential health and social services for older people. This requires strong political commitment and urgent planning.

Second, we must acknowledge that investing in young people today is the best way to improve older people’s lives in the future. But this must be combined with flexible employment, lifelong learning and retraining opportunities to enable and encourage current generations of older people to remain in the labour market.

It’s time to invest in older people

Finally, we must involve everyone including governments, civil society, communities, families and older people themselves to develop a new culture in which older people are considered active members of their society and recognised for their contributions.

The report makes clear that all governments and societies, even those who are pioneers, must raise their game. It also shows that for those making the right investments to ensure dignified ageing; the rewards can far outweigh the costs.

Population ageing should not be seen as a crisis, but as a celebration and a challenge. If governments make the necessary reforms, it can become a huge social and economic opportunity for the benefit of all.