“All human beings are all born free and equal in dignity and rights” – Article 1, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Seventy years on and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights remains as important as ever. Article 1 is still as inspiring and progressive now as it was in 1948.

But as groundbreaking as the UDHR was, it did fail to recognise ageism and prohibit the age discrimination we are subjected to in older age. As a result, older people’s human rights are invisible in international human rights law, in national law, in policies and in our day-to-day lives.

Only one of the nine international human rights treaties that have followed the UDHR explicitly prohibits age discrimination. A mere 177, or 0.3%, of the 57,686 recommendations made to date in the Universal Periodic Review process at the Human Rights Council have been on older people’s rights.

Age discrimination is still not prohibited in many national constitutions and not covered in anti-discrimination laws.

Other laws, policies and practices continue to limit older people’s autonomy, increase their dependency on others and deprive them of their dignity.

We see this in pension policies that are not universal or guaranteed in law, and where the value of the pension is so low older people continue to be financially dependent on others. We see it in mandatory retirement ages that exclude older people from the workforce. We see it in upper age limits that deny older people access to health services, financial goods and services. And older people rarely have choice or control over the care and support they may need to live independently. It is often unavailable, unaffordable and not guaranteed in law.

Seventy years on from the UDHR, older people say they are stereotyped as unable to make their own decisions, incompetent and a burden.

As an older woman from Nigeria said, “A retired teacher like me, I was rejected in more than five private schools because they said I am too old to be of any use.”

Or take the experience of an older man from Uganda: “I am considered a spent force with nothing left to contribute to society, that I have had my turn and should give way to the youth.”

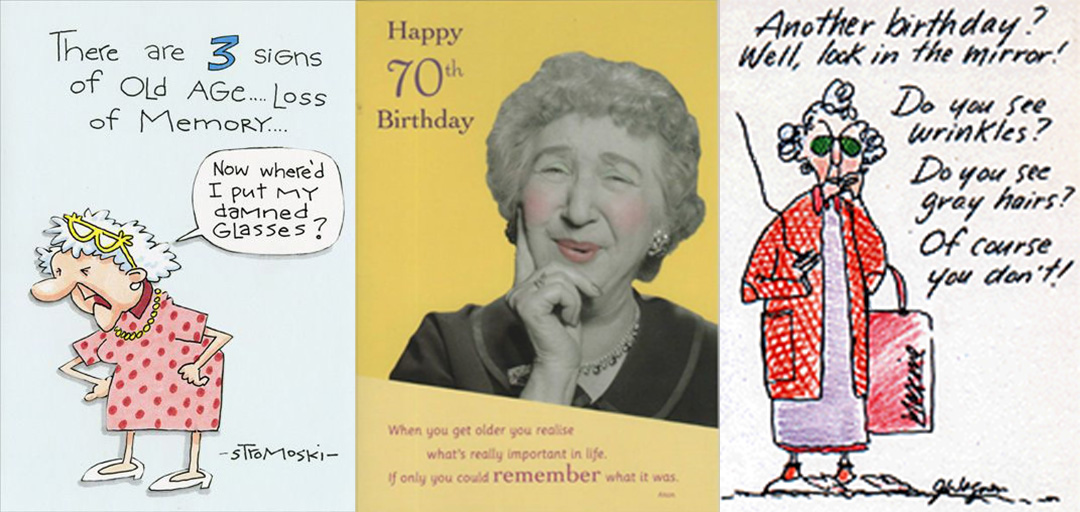

We live in a deeply ageist world where stigmatising and dehumanising prejudices and stereotypes about older people and older age are barely recognised for what they are. They are ignored, tolerated or even condoned, and have very harmful consequences in people’s lives.

Would we still be sending ageist birthday cards like these, and finding them funny, if the UDHR had recognised age discrimination?

Fortunately human rights law is not static. It continues to evolve and respond to different forms of discrimination and deprivations of dignity as they are exposed, or as we better understand them. The failure of the international human rights system to address our rights in older age has been acknowledged at the UN, and the need for a new UN convention on the rights of older people is now firmly on the agenda.

Our rights do not change as we get older. We remain free and equal in dignity and rights whatever our age. What better way to celebrate 70 years of the UDHR than recognition of this in a UN convention on the rights of older people?

Watch our animation on older people and human rights.